Most Australians have seen – or at least heard about – the appalling suffering endured by millions of animals, particularly sheep and cattle, who are crammed into filthy live-export ships and transported for days or weeks in sweltering heat across the equator to Asia and the Middle East. When they arrive, those who’ve survived the journey are slaughtered, often in ways that would be deemed criminal in Australia.

But there’s another form of abuse involved which even the most short-sighted government department cannot ignore: the atrocious human rights violations endured by the crews of these death ships.

Dr Lynn Simpson worked as a veterinarian on such vessels for many companies, under many flags, for over a decade. In addition to exposing animal abuse as an eyewitness from inside the ships, she’s also highlighted the safety concerns which have the potential to cause – or have already led to – serious issues for the crews.

Vessel Instability Causes Injuries

One major problem faced on sea voyages is the stability of the vessel as it encounters different wave and weather conditions and as its weight changes with the animals’ consumption of food and water. If these factors are ignored – and, Simpson says, they usually are – a sudden rapid roll can injure animals and make working in the pens dangerous for crew members, while even a slow roll can be accentuated as animals move around to try to achieve a stable footing.

Crews Exposed to Potentially Toxic Gases

Crew members on live-export ships are expected to work 12-hour shifts – generally from 6 am to 6 pm. On deck, they’re exposed (as are the animals) to dangerous levels of ammonia, carbon dioxide, and highly flammable methane – from the animals themselves and their waste. While these gas build-ups are known to increase dramatically – particularly in hot weather – live-export ships don’t monitor or log toxic-gas levels, even though this is a basic precaution taken on most other vessels, including car carriers.

No On-Board Doctor

On the voyages undertaken by Simpson, there was no medical doctor on board the ships. As a veterinarian, she was often called upon to treat sick and injured crew members.

“I sewed people up, replaced dislocated shoulders, reattached a nearly ripped off thumb. I likely saved an officer from losing his leg to gangrene”, she says.

Crew members who collapsed from heat stress were given IV fluids that Simpson made herself from catheters that she brought with her. None were ever provided on the ships.

Disturbing Crew ‘Initiations’ and Worrying Infections

Traditionally, crew members on their first voyage undergo an initiation, in which “animal sewerage” and “the odd body part” are dumped on blindfolded workers for about an hour. Afterwards, high-pressure hoses are used to clean them off – running the risk of driving bacteria deep into the ears, eyes, nose, and mouth.

On return voyages, crew members are expected to clean excrement from the ships using those same hoses. Sometimes, they have only filthy water available to bathe in afterwards. This often causes open wounds on their bodies to become infected.

Inadequate Disease Prevention

Crew members – especially those working on long contracts – often don’t know where they’re going. This gives them no chance to research destinations and obtain the appropriate vaccinations.

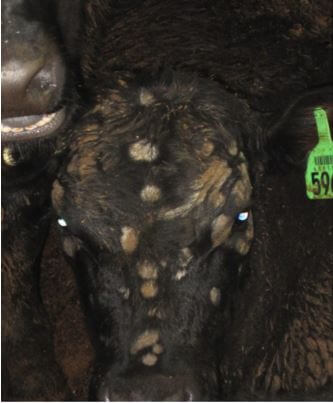

Ringworm – which can be passed from cattle to humans – is commonly contracted. In fact, Simpson says that “[r]ingworm was on nearly every cattle voyage I did, regardless of it being a rejection criterion”.

“Scabby mouth”, which is contracted by sheep and causes painful scabs on the lips, is also a rejection criterion – however, Simpson said it was “always present”. This can develop into a disease in humans called “orf”, which causes painful scabbing on the hands.

Other common diseases on these voyages include salmonellosis, a cause of diarrhoea; conjunctivitis of varying degrees; and leptospirosis, which is spread by cattle urine and can lead to kidney failure.

Dangerous Temperatures Not Effectively Monitored

High temperatures on deck and around equipment are also a serious health risk. While crew members working in the engine room have short shifts and regular respite, those in extremely hot areas such as the fodder tanks – where the animals’ food is stored – don’t have such arrangements in place.

Even the temperatures on deck – which must be endured by workers during their shifts and by the animals constantly – are monitored by just one thermometer on each deck and only for the noon report, well before the day’s maximum temperature has been reached. This information is sent to the Department of Agriculture each day and gives a misleading picture of the conditions experienced by the crew and the animals.

Security Concerns

Although ships have alarms in place, the considerable noise produced by the ventilation system, food and water delivery mechanisms, and the animals themselves make it likely that, in the case of an emergency, alarms signalling fire, piracy, or the instruction to abandon ship wouldn’t be heard.

“What shocked me most [about live export] was the disregard for humanity and the poor conditions that many seafarers are forced to endure. Not just on live animal export ships, but also on many I witnessed in ports we worked in.” – Dr Lynn Simpson

Live export is an industry in its death throes as the public becomes aware of its many forms of abuse and concerned politicians defy their parties to speak out for reform.

Companies’ attempts to minimise their costs in the hope of maintaining profitability come at the expense of not only the lives of the animals on board but also the welfare and rights of the crews.

It’s time the industry was shut down.

Help Animals in 2025: Renew Your PETA Membership!