Bad Ethics and Bad Science: Killing Sharks After Attacks Is Cruel and Pointless Revenge

While it’s upsetting to see footage of two people being rushed to hospital after shark attacks in the Whitsundays last week, the kneejerk response of the government has been panicked and pointless.

Six sharks have been killed in the space of a week, with no evidence that any human has been made safer as a result.

Within 24 hours of the second shark attack, Queensland’s Department of Agriculture and Fisheries had dropped drum lines – large baited hooks – into the water.

Sharks have inhabited the oceans for about 450 million years and should have the right to live in their natural habitat without being hunted and killed. Last year, there were only five fatal unprovoked shark attacks recorded globally, even though millions of humans entered the oceans, often to do dangerous things. In Australia, an average of 280 humans drown every year in waterways, yet this receives far less attention from authorities.

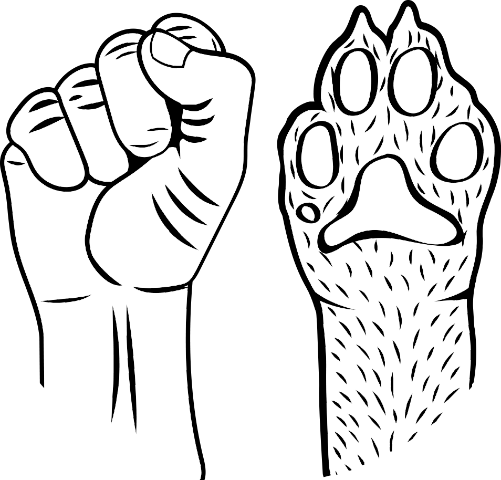

Humans pose a far greater threat to sharks than they ever will to us. Every year, humans pull roughly 100 million sharks from the water, cut off their fins to make soup, and throw their mutilated bodies back into the sea to bleed slowly to death. Many others get caught in the nets of huge fishing trawlers.

The six sharks killed in the Whitsundays aren’t the only ones to be killed by government-sanctioned drum lines. Queensland’s Shark Control Program caught more than 500 sharks in 2017, along with a number of “non-target species”, including whales, turtles, and dolphins, many of whom died before they could be rescued and released.

Sharks play an essential role in our oceans, and interfering with their populations in this way could be ecologically damaging. There is no scientific evidence to support the slaughter of sharks as a solution to rare fatal attacks on humans.

To know more about why shark attacks occur and how we can best avoid them in the future, taxpayers’ money would be better spent on research, not revenge. We should also invest in initiatives such as increased surveillance, the development of shark deterrents, and better public education about avoiding incidents between sharks and humans.

Polls have consistently shown that an overwhelming number of Australians oppose the culling of sharks.

In almost every case of a shark attack, humans quickly go back into the water – often before beaches are officially reopened – well aware that the sharks in the water present an infinitesimally smaller risk to them than driving their cars to the beach does.

The oceans are not ours to plunder. Please share this post on Facebook if you agree:

Help Animals in 2025: Renew Your PETA Membership!