Science should save lives, not take them

Poppy and Alvin should have spent their days going for walks, sniffing around trees, chasing tennis balls, rolling in the grass, napping in cosy beds, and doing all the other things that dogs love. Instead, the two beagles were used as laboratory equipment in experiments for topical skin treatments. By the time they were surrendered to a rescue group, they were overweight (likely from being deprived of exercise), suffering from numerous skin problems, and terrified of being touched.

Thankfully, the dogs are recovering from their ordeal, but millions of other animals never get that chance. They die just as they lived, if it can be called “living”: often alone, afraid, and in terrible pain, locked away in laboratories across Australia.

On 24 April – World Day for Animals in Laboratories – we remember them.

In 2015 – the latest year for which estimates are available – approximately 5.8 million animals were bred or used in experiments nationwide. Each one of them is (or was) an individual – with a heart, a unique personality, a family, and a yearning to live and be free.

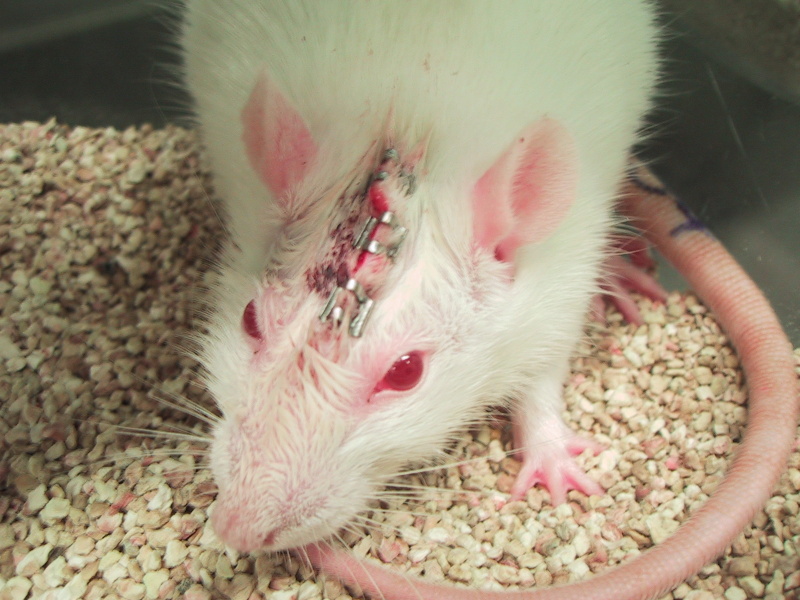

Lab workers addict monkeys to drugs, drill holes into their skulls, burn off the skin of sheep and pigs, crush rats’ spinal cords, grow tumours on tiny mice as large as their own bodies, blind kittens, and give rats seizures.

Thousands of animals are used in lethal procedures such as LD50 tests – in which a group of animals is bombarded with a substance until half of them die or are euthanized. Others are given major infections or cancer, starved, or kept in solitary confinement.

Animals can suffer and feel pain and fear, just as humans can, but physiological responses during experiments differ vastly among species, which makes it virtually impossible to apply the results of tests on one species to another. The US Food and Drug Administration has admitted that nine out of 10 experimental drugs fail in human trials.

But there is hope. Progressive scientists are rejecting inaccurate and misleading data from experiments on animals and embracing superior, humane, human-relevant methods. Harvard’s Wyss Institute has created “organs-on-chips” lined with human cells that can be used instead of animals in drug testing and development. Models made with human skin cultures can spare rabbits the agony of skin corrosion tests. And computer-based models called “QSARs” can make sophisticated estimates of the likelihood that a substance will be hazardous.

Lifelike computerised human-patient simulators breathe, bleed, convulse, talk, and even “die” and have been shown to teach life-saving skills as well as or better than courses that require students to mutilate and kill live dogs, goats, or pigs. After a nearly four-year campaign by PETA, PETA US, and Humane Research Australia, the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons agreed to use such devices instead of mutilating and killing animals.

It’s 2018 – there’s no excuse for condemning living, feeling beings like Poppy and Alvin to miserable lives in cages, painful procedures, and early deaths, especially since superior, human-relevant test methods can be used instead. It’s time that every health charity, company, and university modernised by embracing science that saves – not takes – lives.

Help Animals in 2025: Renew Your PETA Membership!